Applications for the LAMP Fellowship 2025-26 will open soon. Sign up here to be notified when the dates are announced.

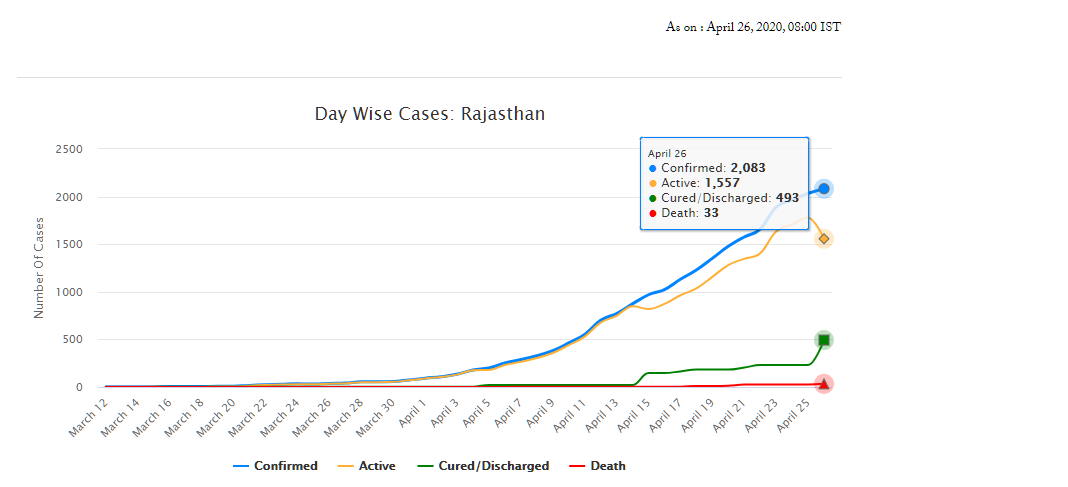

As of April 26, Rajasthan has 2,083 confirmed cases of COVID-19 (fifth highest in the country), of which 493 have recovered and 33 have died. On March 18, the Rajasthan government had declared a state-wide curfew till March 31, to check the spread of the disease. A nation-wide lockdown has also been in place since March 25 and is currently, extended up to May 3. The state has announced several policy decisions to prevent the spread of the virus and provide relief for those affected by it. This blog summarises the key policy measures taken by the Government of Rajasthan in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Early measures for containment

Between late January and early February, Rajasthan Government’s measures were aimed towards identification, screening and testing, and constant monitoring of passenger arrivals from China. Instructions were also issued to district health officials for various prevention, treatment, & control related activities, such as (i) mandatory 28-day home isolation for all travellers from China, (ii) running awareness campaigns, and (iii) ensuring adequate supplies of Personal Protection Equipments (PPEs). Some of the other measures, taken prior to the state-wide lockdown, are summarised below:

Administrative measures

The government announced the formation of Rapid Response Teams (RRTs), at the medical college-level and at district-level on March 3 and 5, respectively.

The District Collector was appointed as the Nodal Officer for all COVID-19 containment activities. Control Rooms were to be opened at all Sub-divisional offices. The concerned officers were also directed to strengthen information dissemination mechanisms and tackle the menace of fake news.

Directives were issued on March 11 to rural health workers/officials to report for duty on Gazetted holidays. Further, government departments were shut down between March 22 and March 31. Only essential departments such as Health Services were allowed to function on a rotation basis at 50% capacity and special / emergency leaves were permitted.

Travel and Movement

Air travellers were to undergo 14-day home isolation and were also required to provide an undertaking for the same. Besides, those violating the mandated isolation/quarantine were liable to be punished under Section. 188 of the Indian Penal Code. Penalties are imposed under this section on persons for the willful violation of orders that have been duly passed by a public servant.

All institutions and establishments, such as (i) educational institutions, theatres, and gyms, (ii) anganwadis, (iii) bars, discos, libraries, restaurants etc, (iv) museums and tourist places, were directed to be shut down till March 31.

The daily Jan Sunwai at the Chief Minister’s residence was cancelled until further notice. Various government offices were directed to shut down and exams of schools and colleges were postponed.

On March 24, the government issued a state-wide ban on the movement of private vehicles till March 31.

Health Measures

Advisories regarding prevention and control measures were issued to: (i) District Collectors, regarding sample collection and transportation, hotels, and preparedness of hospitals, (ii) Police department, to stop using breath analysers, (iii) Private hospitals, regarding preparedness and monitoring activities, and (iv) Temple trusts, to disinfect their premises with chemicals.

The government issued Standard Operating Procedures for conducting mock drills in emergency response handling of COVID-19 cases. Training and capacity building measures were also initiated for (i) Railways, Army personnel etc and (ii) ASHA workers, through video conferencing.

A model micro-plan for containing local transmission of COVID was released. Key features of the plan include: (i) identification and mapping of affected areas, (ii) activities for prevention control, surveillance, and contact tracing, (iii) human resource management, including roles and responsibilities, (iv) various infrastructural and logistical support, such as hospitals, labs etc, and (v) communication and data management.

Resource Management: Private hospitals and medical colleges were instructed to reserve 25 % of beds for COVID-19 patients. They were also instructed to utilise faculty from the departments of Preventive and Social Medicine to conduct health education and awareness activities.

Over 6000 Students of nursing schools were employed in assisting the health department to conduct screening activities being conducted at public places, railways stations, bus stands etc.

Further, the government issued guidelines to ensure the rational use of PPEs.

Welfare Measures

The government announced financial assistance, in the form of encouragement grants, to health professionals engaged in treating COVID-19 patients.

Steps were also taken by the government to ensure speedy disbursal of pensions for February and March.

The government also initiated the replacement of the biometric authentication with an OTP process for distribution of ration via the Public Distribution System (PDS).

During the lockdown

State-wide curfew announced on March 18 has been followed by a nation-wide lockdown between March 25 and May 3. However, certain relaxations have been recommended by the state government from April 21 onwards. Some of the key measures undertaken during the lockdown period are:

Administrative Measures

Advisory groups and task forces were set up on – (i) COVID-19 prevention, (ii) Health and Economy, and (iii) Higher education. These groups will provide advice on the way forward for (i) prevention and containment activities, (ii) post-lockdown strategies and strategies to revive the economy, and (iii) to address the challenges facing the higher education sector respectively.

Services of retiring medical and paramedical professionals retiring between March and August have been extended till September 2020.

Essential Goods and Services

A Drug Supply Control Room was set up at the Rajasthan Pharmacy Council. This is to ensure uninterrupted supply of medicines during the lockdown and will also assist in facilitating home delivery of medicines.

The government permitted Fair Price Shops to sell products such as masalas, sanitisers, and hygiene products, in addition to food grains.

Village service cooperatives were declared as secondary markets to facilitate farmers to sell their produce near their own fields/villages during the lockdown.

A Whatsapp helpline was also set up for complaints regarding hoarding, black marketing, and overpricing.

Travel and Movement

Once lockdown was in place, the government issued instructions to identify, screen, and categorise people from other states who have travelled to Rajasthan. They were to be categorised into: (i) people displaying symptoms to be put in isolation wards, (ii) people over 60 years of age with symptoms and co-morbidities to be put in quarantine centres, and (iii) asymptomatic people to be home quarantined.

On March 28, the government announced the availability of buses to transport people during the lockdown. Further, stranded students in Kota were allowed to return to their respective states.

On April 2, a portal and a helpline were launched to help stranded foreign tourists and NRIs.

On April 11, an e-pass facility was launched for movement of people and vehicles.

Health Measures

To identify COVID-19 patients, district officials were instructed to monitor people with ARI/URI/Pneumonia or other breathing difficulties coming into hospital OPDs. Pharmacists were also instructed to not issue medicines for cold/cough without prescriptions.

A mobile app – Raj COVID Info – was developed by the government for tracking of quarantined people. Quarantined persons are required to send their selfie clicks at regular intervals, failing which a notification would be sent by the app. The app also provides a lot of information on COVID-19, such as the number of cases, and press releases by the government.

Due to the lockdown, people had restricted access to hospitals and treatment. Thus, instructions were issued to utilise Mobile Medical Vans for treatment/screening and also as mobile OPDs.

On April 20, a detailed action plan for prevention and control of COVID-19 was released. The report recommended: (i) preparation of a containment plan, (ii) formation of RRTs, (iii) testing protocols, (iv) setting up of control room and helpline, (v) designated quarantine centres and COVID-19 hospitals, (vi) roles and responsibilities, and (vii) other logistics.

Welfare Measures

The government issued instructions to make medicines available free of cost to senior citizens and other patients with chronic illnesses through the Chief Minister’s Free Medicine Scheme.

Rs 60 crore was allotted to Panchayati Raj Institutions to purchase PPEs and for other prevention activities.

A one-time cash transfer of Rs 1000 to over 15 lakh construction workers was announced. Similar cash transfer of Rs 1000 was announced for poor people who were deprived of livelihood during the lockdown, particularly those people with no social security benefits. Eligible families would be selected through the Aadhaar database. Further, an additional cash transfer of Rs 1500 to needy eligible families from different categories was announced.

The state also announced an aid of Rs 50 lakh to the families of frontline workers who lose their lives due to COVID-19.

To maintain social distancing, the government will conduct a door-to-door distribution of ration to select beneficiaries in rural areas of the state. The government also announced the distribution of free wheat for April, May, and June, under the National Food Security Act, 2013. Ration will also be distributed to stranded migrant families from Pakistan, living in the state.

The government announced free tractor & farming equipment on rent in tie-up with farming equipment manufacturers to assist economically weak small & marginal farmers.

Other Measures

Education: Project SMILE was launched to connect students and teachers online during the lockdown. Study material would be sent through specially formed Whatsapp groups. For each subject, 30-40 minute content videos have been prepared by the Education Department.

Industry: On April 18, new guidelines were issued for industries and enterprises to resume operations from April 20 onwards. Industries located in rural areas or export units / SEZs in municipal areas where accommodation facilities for workers are present, are allowed to function. Factories have been permitted to increase the working hours from 8 hours to 12 hours per day, to reduce the requirement of workers in factories. This exemption has been allowed for the next three months for factories operating at 60% to 65% of manpower capacity.

For more information on the spread of COVID-19 and the central and state government response to the pandemic, please see here.

A few weeks ago, in response to the initial protests by farmers against the new central farm laws, three state assemblies – Chhattisgarh, Punjab, and Rajasthan – passed Bills to address farmers’ concerns. While these Bills await the respective Governors’ assent, protests against the central farm laws have gained momentum. In this blog, we discuss the key amendments proposed by these states in response to the central farm laws.

What are the central farm laws and what do they seek to do?

In September 2020, Parliament enacted three laws: (i) the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, (ii) the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, and (iii) the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020. The laws collectively seek to: (i) facilitate barrier-free trade of farmers’ produce outside the markets notified under the various state Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) laws, (ii) define a framework for contract farming, and (iii) regulate the supply of certain food items, including cereals, pulses, potatoes, and onions, only under extraordinary circumstances such as war, famine, and extraordinary price rise.

How do the central farm laws change the agricultural regulatory framework?

Agricultural marketing in most states is regulated by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs), set up under the state APMC Act. The central farm laws seek to facilitate multiple channels of marketing outside the existing APMC markets. Many of these existing markets face issues such as limited number of buyers restricting the entry of new players and undue deductions in the form of commission charges and market fees. The central laws introduced a liberalised agricultural marketing system with the aim of increasing the availability of buyers for farmers’ produce. More buyers would lead to competition in the agriculture market resulting in better prices for farmers.

Why have states proposed amendments to the central farm laws?

The central farm laws allow anyone with a PAN card to buy farmers’ produce in the ‘trade area’ outside the markets notified or run by the APMCs. Buyers do not need to get a license from the state government or APMC, or pay any tax to them for such purchase in the ‘trade area’. These changes in regulations raised concerns regarding the kind of protections available to farmers in the ‘trade area’ outside APMC markets, particularly in terms of the price discovery and payment. To address such concerns, the states of Chhattisgarh, Punjab, and Rajasthan, in varying forms, proposed amendments to the existing agricultural marketing laws.

The Punjab and Rajasthan assemblies passed Bills to amend the central Acts, in their application to these states. The Chhattisgarh Assembly passed a Bill to amend its APMC Act in response to the central Acts. These state Bills aim to prevent exploitation of farmers and ensure an optimum guarantee of fair market price for the agriculture produce. Among other things, these state Bills enable state governments to levy market fee outside the physical premises of the state APMC markets, mandate MSP for certain types of agricultural trade, and enable state governments to regulate the production, supply, and distribution of essential commodities and impose stock limits under extraordinary circumstances.

Chhattisgarh

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 allows anyone with a PAN card to buy farmers’ produce in the trade area outside the markets notified or run by the APMCs. Buyers do not need to get a license from the state government or APMC, or pay any tax to them for such purchase in the trade area. The Chhattisgarh Assembly passed a Bill to amend its APMC Act to allow the state government to notify structures outside APMC markets, such as godowns, cold storages, and e-trading platforms, as deemed markets. This implies that such deemed markets will be under the jurisdiction of the APMCs as per the central Act. Thus, APMCs in Chhattisgarh can levy market fee on sale of farmers’ produce in such deemed markets (outside the APMC markets) and require the buyer to have a license.

Punjab and Rajasthan

The Punjab and Rajasthan Bills empower the respective state governments to levy a market fee (on private traders, and electronic trading platforms) for trade outside the state APMC markets. Further, they mandate that in certain cases, agricultural produce should not be sold or purchased at a price below the Minimum Support Price (MSP). For instance, in Punjab sale and purchase of wheat and paddy should not be below MSP. The Bills also provide that they will override any other law currently in force. Table 1 gives a comparison of the amendments proposed by states with the related provisions of the central farm laws.

Table 1: Comparison of the central farm laws with amendments proposed by Punjab and Rajasthan

|

Provision |

Central laws |

State amendments |

|

Market fee |

|

|

|

Minimum Support Price (MSP) - fixed by the central government, based on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices |

|

|

|

Penalties for compeling farmers to sell below MSP |

|

|

|

Delivery under farming agreements |

|

|

|

Regulation of essential commodities |

|

|

|

Imposition of stock limit |

|

|

|

Dispute Resolution Mechanism for Farmers |

|

|

|

Power of civil courts |

|

|

|

Special provisions |

|

|

Note: A market committee provides facilities for and regulates the marketing of agricultural produce in a designated market area.

Have the state amendments come into force?

The amendments proposed by states aim to address the concerns of farmers, but to a varying extent. The Bills have not come into force yet as they await the Governors’ assent. In addition, the Punjab and Rajasthan Bills also need the assent of the President, as they are inconsistent with the central Acts and seek to amend them. Meanwhile, amidst the ongoing protests, many farmers’ organisations are in talks with the central government to seek redressal of their grievances and appropriate changes in the central farm laws. It remains to be seen to what extent will such changes address the concerns of farmers.

A version of this article first appeared on Firstpost on December 5, 2020.