The central government has enforced a nation-wide lockdown between March 25 and May 3 as part of its measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. During the lockdown, several restrictions have been placed on the movement of individuals and economic activities have come to a halt barring the activities related to essential goods and services. The restrictions are being relaxed in less affected areas in a limited manner since April 20. In this blog, we look at how the lockdown has impacted the demand and supply of electricity and what possible repercussions its prolonged effect may have on the power sector.

Power supply saw a decrease of 25% during the lockdown (year-on-year)

As electricity cannot be stored in large amount, the power generation and supply for a given day are planned based on the forecast for demand. The months of January and February in 2020 had seen an increase of 3% and 7% in power supply, respectively as compared to 2019 (year-on-year). In comparison, the power supply saw a decrease of 3% between March 1 and March 24. During the lockdown between March 24 and April 19, the total power supply saw a decrease of about 25% (year-on-year).

Figure 1: % change in power supply position between March 1 and April 19 (Y-o-Y from 2019 to 2020)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

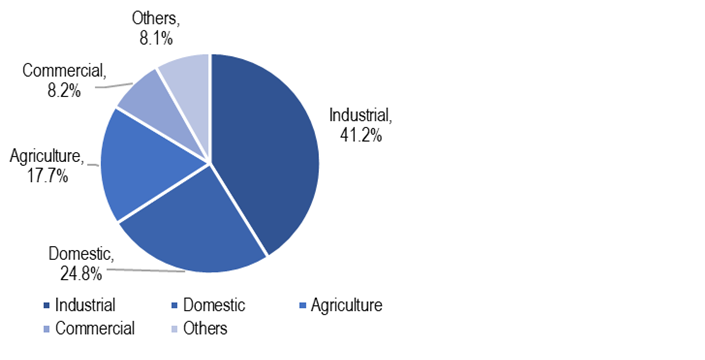

If we look at the consumption pattern by consumer category, in 2018-19, 41% of total electricity consumption was for industrial purposes, followed by 25% for domestic and 18% for agricultural purposes. As the lockdown has severely reduced the industrial and commercial activities in the country, these segments would have seen a considerable decline in demand for electricity. However, note that the domestic demand may have seen an uptick as people are staying indoors.

Figure 2: Power consumption by consumer segment in 2018-19

Sources: Central Electricity Authority; PRS.

Electricity demand may continue to be subdued over the next few months. At this point, it is unclear that when lockdown restrictions are eased, how soon will economic activities return to pre COVID-19 levels. India’s growth projections also highlight a slowdown in the economy in 2020 which will further impact the demand for electricity. On April 16, the International Monetary Fund has slashed its projection for India’s GDP growth in 2020 from 5.8% to 1.9%.

A nominal increase in energy and peak deficit levels

As power sector related operations have been classified as essential services, the plant operations and availability of fuel (primarily coal) have not been significantly constrained. This can be observed with the energy deficit and peak deficit levels during the lockdown period which have remained at a nominal level. Energy deficit indicates the shortfall in energy supply against the demand during the day. The average energy deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.42% while the corresponding figure was 0.33% between March 1 and March 24. Similarly, the average peak deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.56% as compared to 0.41% between March 1 and March 24. Peak deficit indicates the shortfall in supply against demand during highest consumption period in a day.

Figure 3: Energy deficit and peak deficit between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in %)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Coal stock with power plants increases

Coal is the primary source of power generation in the country (~71% in March 2020). During the lockdown period, the coal stock with coal power plants has seen an increase. As of April 19, total coal-stock with the power plants in the country (in days) has risen to 29 days as compared to 24 days on March 24. This indicates that the supply of coal has not been constrained during the lockdown, at least to the extent of meeting the requirements of power plants.

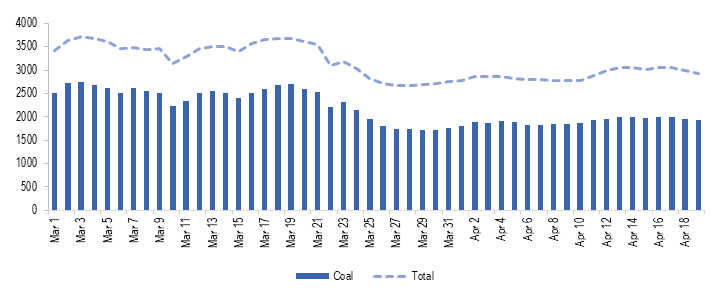

Energy mix changes during the lockdown, power generation from coal impacted

During the lockdown, power generation has been adjusted to compensate for reduced consumption, Most of this reduction in consumption has been adjusted by reduced coal power generation. As can be seen in Table 1, coal power generation reduced from an average of 2,511 MU between March 1 and March 24 to 1,873 MU between March 25 and April 19 (about 25%). As a result, the contribution of coal in total power generation reduced from an average of 72.5% to 65.6% between these two periods.

Table 1: Energy Mix during March 1-April 19, 2020

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

This shift may be happening due to various reasons including: (i) renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and small hydro) have MUST RUN status, i.e., the power generated by them has to be given the highest priority by distribution companies, and (ii) running cost of renewable power plants is lower as compared to thermal power plants.

This suggests that if growth in electricity demand were to remain weak, the adverse impact on the coal power plants could be more as compared to other power generation sources. This will also translate into weak demand for coal in the country as almost 87% of the domestic coal production is used by the power sector. Note that the plant load factor (PLF) of the thermal power plants has seen a considerable decline over the years, decreasing from 77.5% in 2009-10 to 56.4% in 2019-20. Low PLF implies that coal plants have been lying idle. Coal power plants require significant fixed costs, and they incur such costs even when the plant is lying idle. The declining capacity utilisation augmented by a weaker demand will undermine the financial viability of these plants further.

Figure 4: Power generation from coal between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in MU)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Finances of the power sector to be severely impacted

Power distribution companies (discoms) buy power from generation companies and supply it to consumers. In India, most of the discoms are state-owned utilities. One of the key concerns in the Indian power sector has been the poor financial health of its discoms. The discoms have had high levels of debt and have been running losses. The debt problem was partly addressed under the UDAY scheme as state governments took over 75% of the debt of state-run discoms (around 2.1 lakh crore in two years 2015-16 and 2016-17). However, discoms have continued to register losses owing to underpricing of electricity tariff for some consumer segments, and other forms of technical and commercial losses. Outstanding dues of discoms towards power generation companies have also been increasing, indicating financial stress in some discoms. At the end of February 2020, the total outstanding dues of discoms to generation companies stood at Rs 92,602 crore.

Due to the lockdown and its further impact in the near term, the financial situation of discoms is likely to be aggravated. This will also impact other entities in the value chain including generation companies and their fuel suppliers. This may lead to reduced availability of working capital for these entities and an increase in the risk of NPAs in the sector. Note that, as of February 2020, the power sector has the largest share in the deployment of domestic bank credit among industries (Rs 5.4 lakh crore, 19.3% of total).

Following are some of the factors which have impacted the financial situation during the lockdown:

Reduced cross-subsidy: In most states, the electricity tariff for domestic and agriculture consumers is lower than the actual cost of supply. Along with the subsidy by the state governments, this gap in revenue is partly compensated by charging industrial and commercial consumers at a higher rate. Hence, industrial and commercial segments cross-subsidise the power consumption by domestic and agricultural consumers.

The lockdown has led to a halt on commercial and industrial activities while people are staying indoors. This has led to a situation where the demand from the consumer segments who cross-subsidise has decreased while the demand from consumer segments who are cross-subsidised has increased. Due to this, the gap between revenue realised by discoms and cost of supply will widen, leading to further losses for discoms. States may choose to bridge this gap by providing a higher subsidy.

Moratorium to consumers: To mitigate the financial hardship of citizens due to COVID-19, some states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Goa, among others, have provided consumers with a moratorium for payment of electricity bills. At the same time, the discoms are required to continue supplying electricity. This will mean that the return for the supply made in March and April will be delayed, leading to lesser cash in hand for discoms.

Some state governments such as Bihar also announced a reduction in tariff for domestic and agricultural consumers. Although, the reduction in tariff will be compensated to discoms by government subsidy.

Constraints with government finances: The revenue collection of states has been severely impacted as economic activities have come to a halt. Further, the state governments are directing their resources for funding relief measures such as food distribution, direct cash transfers, and healthcare. This may adversely affect or delay the subsidy transfer to discoms.

The UDAY scheme also requires states to progressively fund greater share in losses of discoms from their budgetary resources (10% in 2018-19, 25% in 2019-20, and 50% in 2020-21). As losses of discoms may widen due to the above-mentioned factors, the state government’s financial burden is likely to increase.

Capacity addition may be adversely impacted

As per the National Electricity Plan, India’s total capacity addition target is around 176 GW for 2017-2022. This comprises of 118 GW from renewable sources, 6.8 GW from hydro sources, and 6.4 GW from coal (apart from 47.8 GW of coal-based power projects already in various stages of production as of January 2018).

India has set a goal of installing 175 GW of Renewable Power Capacity by 2022 as part of its climate change commitments (86 GW has been installed as of January 2020). In January 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy observed that India could only install 82% and 55% of its annual renewable energy capacity addition targets in 2017-18 and 2018-19. As of January 2020, 67% of the target has been achieved for 2019-20.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, the capacity addition targets for various sources is likely to be adversely impacted in the short run as:

construction activities were stopped during the lockdown and will take some time to return to normal,

disruption in the global supply chain may lead to difficulties with the availability of key components leading to delay in execution of projects, for instance, for solar power plants, solar PV modules are mainly imported from China, and

reduced revenue for companies due to weak demand will leave companies with less capacity left for capital expenditure.

Key reforms likely to be delayed

Following are some of the important reforms anticipated in 2020-21 which may get delayed due to the developing situation:

The real-time market for electricity: The real-time market for electricity was to be operationalised from April 1, 2020. However, the lockdown has led to delay in completion of testing and trial runs. The revised date for implementation is now June 1, 2020.

UDAY 2.0/ADITYA: A new scheme for the financial turnaround of discoms was likely to come this year. The scheme would have provided for the installation of smart meters and incentives for rationalisation of the tariff, among other things. It remains to be seen what this scheme would be like since the situation with government finances is also going to worsen due to anticipated economic slowdown.

Auction of coal blocks for commercial mining: The Coal Ministry has been considering auction of coal mines for commercial mining this year. 100% FDI has been allowed in the coal mining activity for commercial sale of coal to attract foreign players. However, the global economic slowdown may mean that the auctions may not generate enough interest from foreign as well as domestic players.

For a detailed analysis of the Indian Power Sector, please see here. For details on the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the country and across states, please see here. For details on the major COVID-19 related notifications released by the centre and the states, please see here.

Earlier today, the Union Cabinet announced the merger of the Railways Budget with the Union Budget. All proposals under the Railways Budget will now be a part of the Union Budget. However, to ensure detailed scrutiny, the Ministry’s expenditure will be discussed in Parliament. Further, Railways will continue to maintain its autonomy and financial decision making powers. In light of this, this post discusses some of the ways in which Railways is financed, and issues it faces with regard to financing. Separation of Railways Budget and its financial implications The Railways Budget was separated from the Union Budget in 1924. While the Union Budget looks at the overall revenue and expenditure of the central government, the Railways Budget looks at the revenue and expenditure of the Ministry of Railways. At that time, the proportion of Railways Budget was much higher as compared to the Union Budget. The separation of the Budgets was done to ensure that the central government receives an assured contribution from the Railways revenues. However, in the last few years, Railways’ finances have deteriorated and it has been struggling to generate enough surplus to invest in improving its infrastructure. Indian Railways is primarily financed through budgetary support from the central government, its own internal resources (freight and passenger revenue, leasing of railway land, etc.), and external resources (market borrowings, public private partnerships, joint ventures, or market financing). Every year, all ministries, except Railways, get support from the central government based on their estimated revenue and expenditure for the year. The Railways Ministry is provided with a gross budgetary support from the central government in order to expand its network. However, unlike other Ministries, Railways pays a return on this investment every year, known as dividend. The rate of this dividend is currently at around 5%, and also includes the interest on government budgetary support received in the previous years. Various Committees have observed that the system of receiving support from the government and then paying back dividend is counter-productive. It was recommended that the practice of paying dividend can be avoided until the financial health of Railways improves. In the announcement made today, the requirement to pay dividend to the central government has been removed. This would save the Ministry from the liability of paying around Rs 9,700 crore as dividend to the central government every year. However, Railways will continue to get gross budgetary support from the central government. Declining internal revenue In addition to its core business of providing transportation, Railways also has several social obligations such as: (i) providing certain passenger and coaching services at below cost fares, (ii) running uneconomic branch lines (connectivity to remote areas), and (iii) granting concessions to various categories of people (like senior citizens, children, etc.). All these add up to about Rs 30,000 crore. Other inelastic expenses of Railways include pension charges, fuel expenses, lease payments, etc. Such expenses do not leave any financial room for the Railways to make any infrastructure investments.  In the last few years, Railways has been struggling due to a decline in its revenue from passenger and freight traffic. In addition, the support from the central government has broadly remained constant. In 2015-16, the gross budgetary support and internal revenue saw a decline, while there was some increase in the extra budgetary resources (shown in Figure 1). Railways’ internal revenue primarily comes from freight traffic (about 65%), followed by passenger traffic (about 25%). About one-third of the passenger revenue comes from first class passenger traffic and the remaining two-third comes from second class passenger traffic. In 2015-16, Railways passenger traffic decreased by 4% and total passenger revenue decreased by 10% from the budget estimates. While revenue from second class saw a decrease of 13%, revenue from first class traffic decreased by 3%. In the last few years, Railways’ internal sources have been declining, primarily due to a decline in both passenger as well as freight traffic. Freight traffic

In the last few years, Railways has been struggling due to a decline in its revenue from passenger and freight traffic. In addition, the support from the central government has broadly remained constant. In 2015-16, the gross budgetary support and internal revenue saw a decline, while there was some increase in the extra budgetary resources (shown in Figure 1). Railways’ internal revenue primarily comes from freight traffic (about 65%), followed by passenger traffic (about 25%). About one-third of the passenger revenue comes from first class passenger traffic and the remaining two-third comes from second class passenger traffic. In 2015-16, Railways passenger traffic decreased by 4% and total passenger revenue decreased by 10% from the budget estimates. While revenue from second class saw a decrease of 13%, revenue from first class traffic decreased by 3%. In the last few years, Railways’ internal sources have been declining, primarily due to a decline in both passenger as well as freight traffic. Freight traffic  The share of Railways in total freight traffic has declined from 89% to 30% over the last 60 years, with most of the share moving towards roads (see Figure 2). With regard to freight traffic, Railways generates most of its revenue from the transportation of coal (about 44%), followed by cement (8%), iron ore (7%), and food-grains (7%). In 2015-16, freight traffic decreased by 10%, and freight earnings reduced by 5% from the budget estimates. The Railways Budget for 2016-17 estimates an increase of 12% in passenger revenue and a 0.26% increase in passenger traffic. Achieving a 12% increase in revenue without a corresponding increase in traffic will require an increase in fares. Flexi fares and passenger traffic A few days ago, the Ministry of Railways introduced a flexi-fare system for certain categories of trains. Under this system, the base fare for Rajdhani, Duronto and Shatabdi trains will increase by 10% with every 10% of berths sold, subject to a ceiling of up to 1.5 times the base fare. While this could also be a way for Railways to improve its revenue, it has raised concerns about train fares becoming more expensive. Note that the flexi-fare system will apply only to first class passenger traffic, which contributes to about 8% of the total Railways revenue. It remains to be seen if the new system increases Railways revenue, or further decreases passenger traffic (people choosing other modes of travel, such as airways, if fares increase significantly). While the Railways is trying to improve revenue by raising fares, this may increase the financial burden on passengers. In the past, various Parliamentary Committees have observed that the investment planning in Railways from the government’s side is politically driven rather than need driven. This has resulted in the extension of uneconomic, un-remunerative, yet socially desirable projects in every budget. It has been recommended that projects based on social and commercial considerations must be categorised separately in the Railways accounts, and funding for the former must come from the central or state governments. It has also been recommended that Railways should bring in more accuracy in determining its public service obligations. The decision to merge the Railways Budget with the Union Budget seems to be on the lines of several of these recommendations. However, it remains to be seen whether merging the Railway Budget with the Union Budget will improve the transporter’s finances or if it would require bringing in more reforms.

The share of Railways in total freight traffic has declined from 89% to 30% over the last 60 years, with most of the share moving towards roads (see Figure 2). With regard to freight traffic, Railways generates most of its revenue from the transportation of coal (about 44%), followed by cement (8%), iron ore (7%), and food-grains (7%). In 2015-16, freight traffic decreased by 10%, and freight earnings reduced by 5% from the budget estimates. The Railways Budget for 2016-17 estimates an increase of 12% in passenger revenue and a 0.26% increase in passenger traffic. Achieving a 12% increase in revenue without a corresponding increase in traffic will require an increase in fares. Flexi fares and passenger traffic A few days ago, the Ministry of Railways introduced a flexi-fare system for certain categories of trains. Under this system, the base fare for Rajdhani, Duronto and Shatabdi trains will increase by 10% with every 10% of berths sold, subject to a ceiling of up to 1.5 times the base fare. While this could also be a way for Railways to improve its revenue, it has raised concerns about train fares becoming more expensive. Note that the flexi-fare system will apply only to first class passenger traffic, which contributes to about 8% of the total Railways revenue. It remains to be seen if the new system increases Railways revenue, or further decreases passenger traffic (people choosing other modes of travel, such as airways, if fares increase significantly). While the Railways is trying to improve revenue by raising fares, this may increase the financial burden on passengers. In the past, various Parliamentary Committees have observed that the investment planning in Railways from the government’s side is politically driven rather than need driven. This has resulted in the extension of uneconomic, un-remunerative, yet socially desirable projects in every budget. It has been recommended that projects based on social and commercial considerations must be categorised separately in the Railways accounts, and funding for the former must come from the central or state governments. It has also been recommended that Railways should bring in more accuracy in determining its public service obligations. The decision to merge the Railways Budget with the Union Budget seems to be on the lines of several of these recommendations. However, it remains to be seen whether merging the Railway Budget with the Union Budget will improve the transporter’s finances or if it would require bringing in more reforms.